Written by Miranda Helus

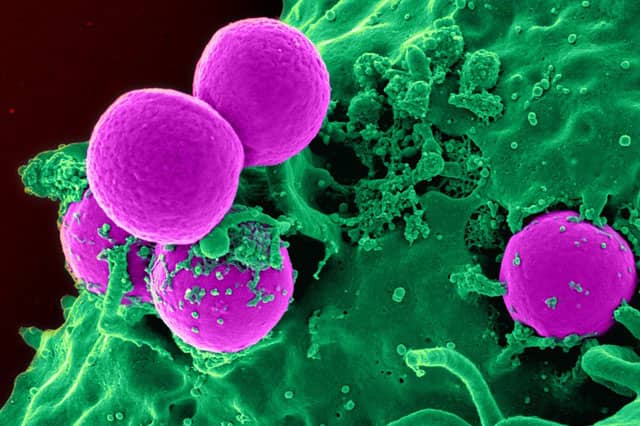

In recent years, immunotherapy has emerged as an individualized and promising candidate for cancer treatment. Immunotherapy aims to boost the immune system’s defenses and induce them to target cancer cells. Several types currently exist, including monoclonal antibody therapy (designing antibodies to target specific cancer cells for destruction) and adoptive T cell transfer (enhancing white blood cells to eliminate cancer cells) [1]. Careful analysis and success in immunotherapy research and clinical tests demonstrate its efficiency and benefits as a potential type of cancer treatment, perhaps one that could replace current treatments like chemotherapy [3]. Despite the breakthroughs, however, availability is limited in terms of speed and patient qualification, and the prospect of presenting immunotherapy as a widespread treatment is confronted with some challenges.

One major obstacle focuses on the limited accessibility of clinical trials to cancer patients. Although certain databases exist as simple methods to search for immunotherapy clinical trials [2], inconveniences can still arise from identifying the most desirable one. One reason is that each clinical trial contains specific qualifications that a patient must fulfill in order to participate, which in turn can be associated with the precise and individualized nature of immunotherapy [3]. Cancers are characterized based on not just the infected organ or tissue but also specific cellular mutations or symptoms ranging in severity. Because of this ever-increasing diversity, eligibility criteria are extremely strict about what sort of cancer the experimental drug is meant to treat and which patients can be accepted under such guidelines [3]. One clinical trial, for example, can only recruit patients diagnosed with GPC3-positive hepatocellular carcinoma rather than just any patient diagnosed with skin cancer [4].

Another complication emphasizes the developmental process of immunotherapy drugs. As new immunotherapy drugs are being created and tested, researchers are wary about the harmful and even potentially deadly side effects they may contain. The looming uncertainty regarding the side effects raises immense concern over drug efficacy and safety, thereby reintroducing the classic moral dilemma in scientific research about whether the benefits outweigh the risks [3]. Common but non-fatal side effects of immunotherapy such as fever and allergic reactions have already been observed [1], along with more harmful side effects such as neural damage, psychosis, coma, and death that have either been predicted or recorded [3]. Drug development in immunotherapy research is also complicated by, as with the clinical trial issue, the highly specialized nature of the treatment. Each new and potential drug must be designed to recognize cancer cells with a very specific mutation. In the past month, for example, scientists have worked to engineer NK-92 (natural killer) cells expressing antigen receptors that will target only certain malignant tumors in cancers like lymphoma [5].

Enormous but gradual progress has been made in establishing immunotherapy as an official, effective cancer treatment. When immunotherapy will finally achieve this final status is unknown and, unfortunately, may take longer than anyone can ever want. For now, as researchers continue their efforts to improve immunotherapy and as the government plans to financially contribute to the cause [3], all the public can do is wait.

References:

1. “Immunotherapy.” National Cancer Institute. 29 Apr. 2015. Web. 7 Apr. 2016.

2. “Search Results.” Clinicaltrials.gov. Web. 7 Apr. 2016.

3. Park A. 2016. Her Chart Said “Two Weeks to Fatal Event.” Ten Years Later, She’s Still Alive. TIME 187: 36–42.

4. “CAR-T Cell Immunotherapy for HCC Targeting GPC3.” Clinicaltrials.gov. Web. 7 Apr. 2016

5. Klingemann H, Boissel L, Toneguzzo F. 2016. Natural Killer Cells for Immunotherapy – Advantages of the NK-92 Cell Line over Blood NK Cells. Front. Immunol. Frontiers in Immunology 7: 91-91.